Electric vs. Gasoline Vehicles: A Lifecycle Emissions Analysis for Canada

Electric vehicles (EVs) are rapidly gaining traction as a key solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector. However, assessing their true environmental impact requires a comprehensive ‘cradle-to-grave’ analysis, considering emissions from manufacturing, fuel production, and vehicle disposal. This report examines the lifecycle emissions of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and gasoline vehicles in Canada, providing insights into their relative environmental performance.

Key Findings

- Reduced Emissions: BEVs generally have significantly lower lifecycle emissions than gasoline vehicles, even in provinces relying on fossil fuel-based electricity generation. The primary driver of this difference is the far greater emissions from gasoline vehicles’ fuel consumption.

- Impact of Electricity Grids: The emissions benefits of EVs hinge on the carbon intensity of the electricity grid. Cleaner grids translate to greater emissions savings for EVs. As grids decarbonize over time, the environmental advantage of EVs will continue to grow.

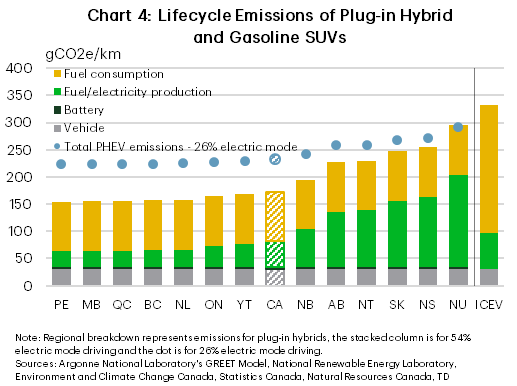

- PHEV Emissions: Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) release fewer emissions than gasoline vehicles, yet their emissions savings are less than those of BEVs. The level of savings depends on the proportion of electric versus gasoline driving.

- Affordability Challenges: The limited availability of affordable EV models and the potential for reduced rebate programs could hamper EV adoption and emissions reduction efforts.

Lifecycle Emissions: A Comprehensive View

Lifecycle emissions consider all emissions linked to a vehicle, including the manufacturing process, raw material extraction, fuel production and consumption, vehicle maintenance, and end-of-life disposal.

Across Canada, BEVs have lower lifetime emissions compared to conventional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). Nationally, the average emissions savings of BEVs ranges from 70% to 77% across different vehicle classes. Notably, this advantage holds even if a BEV’s lithium-ion battery is replaced during its lifespan, though the average emissions savings decrease to 59-69%.

Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) also have reduced emissions relative to ICEVs, but possess less advantage compared to all-electric options. For both BEVs and PHEVs, fuel-related emissions change based on the carbon intensity of the electricity grid used to charge their batteries. This illustrates that the environmental advantage of BEVs and PHEVs will continue to strengthen as electricity grids are decarbonized.

Vehicle Cycle vs. Fuel Cycle Emissions

Lifecycle emissions are divided into two main categories:

- Vehicle cycle emissions: These emissions are those associated with production and include the vehicle’s components such as the battery, maintenance and end-of-life disposal.

- Fuel cycle emissions: These are the emissions relating to fuel consumption, which include electricity, gasoline, or diesel, used to power vehicles.

When comparing 2024 model year vehicles, BEVs tend to have higher vehicle cycle emissions, while fuel cycle emissions are larger for ICEVs. However, the fuel emissions from ICEVs significantly surpass the vehicle cycle emissions of BEVs. Therefore, ICEVs generate higher lifetime emissions than electric vehicles.

Battery Production Emissions

Lithium-ion batteries, which are extremely important to electric vehicles, are responsible for some of the higher vehicle cycle emissions of BEVs. The mining and refining of these minerals, like lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite, are energy-intensive and lead to emissions. Manufacturing components like batteries requires high temperatures, which normally involves burning fossil fuels. Based on estimates, batteries account for approximately half of BEV vehicle cycle emissions. This share can increase to over 60% should the vehicle’s battery be replaced.

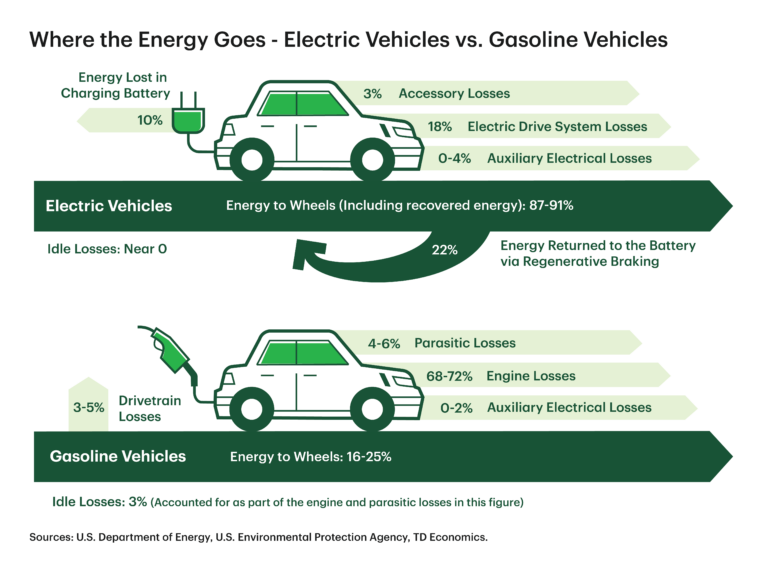

Graphic shows how much of the energy from electricity or gasoline is used to move the vehicle versus lost or used for other purposes.

However, the location of battery production significantly impacts the carbon footprint. For example, battery cells produced in Sweden have emissions that are about a quarter less than those made in China. China’s coal-heavy energy mix plays a defining role in battery emissions due to its dominance in global battery supply chains, but that will decline over time as jurisdictions like Canada increase their market share.

The Efficiency Advantage of Electric Motors

BEVs are more energy efficient during operation: gasoline vehicles use considerably more energy to travel the same distance.

The difference in energy efficiency is considerable, with 16-25% of the energy in gasoline being used to move an ICEV versus 87-91% of the energy in electricity for a BEV.

For example, compared to models from 2024, gasoline SUVs use 6.7-21.7 litres of gasoline by 100 km, while electric versions use 20.9-44.6 kWh, which is equivalent to 2.3-5 litres of gasoline in terms of energy content.

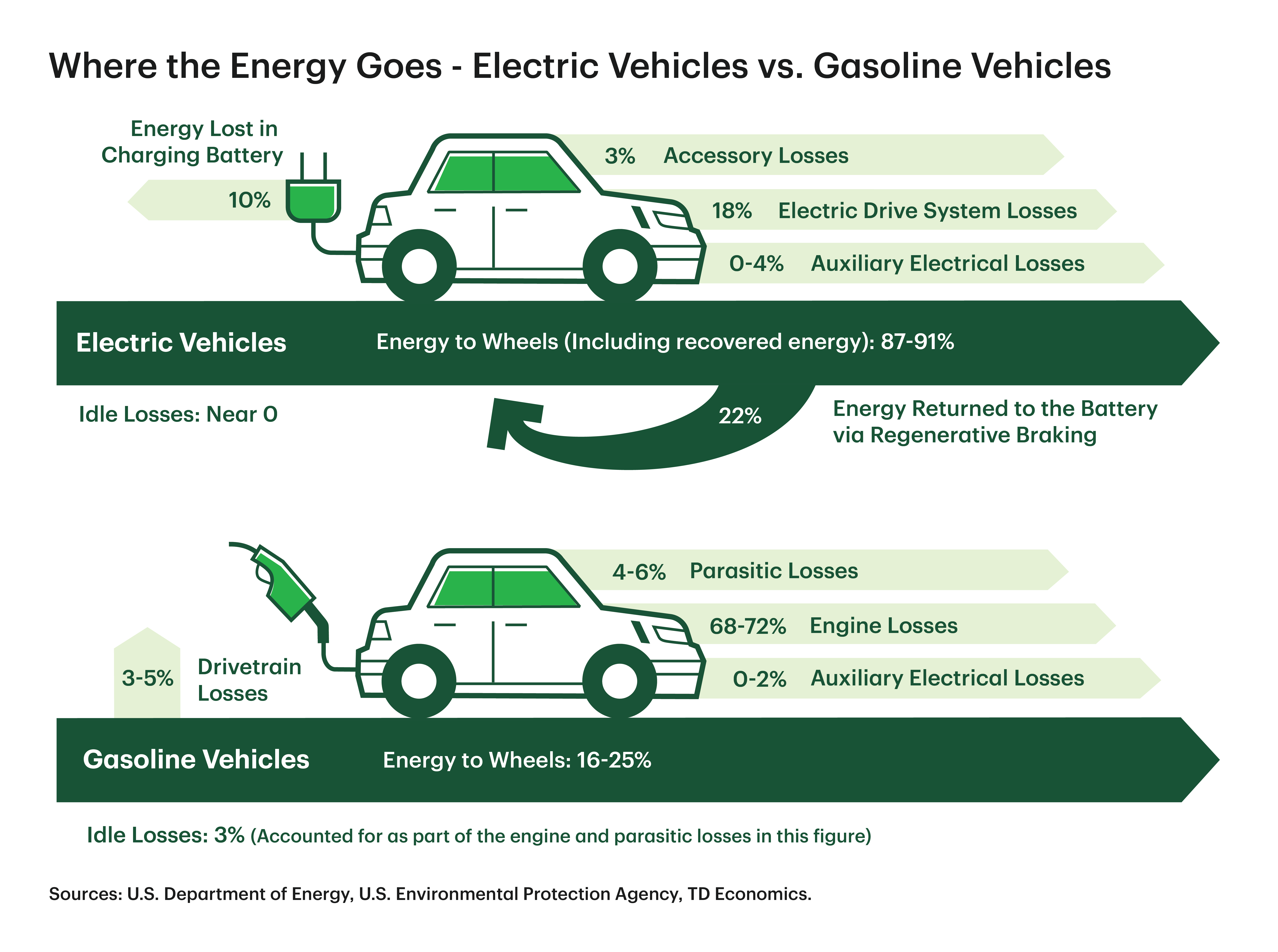

Chart 2 compares lifecycle emissions of gasoline and electricity in Canada.

Electric vehicles benefit from the low-emissions intensity of electricity generation over gasoline in most areas of Canada. At the national level, the emissions from grid electricity are 61% lower than those from gasoline, and 20%-93% lower across the eight provinces and territories with cleaner grid electricity.

Regional Variations in Emissions Benefits

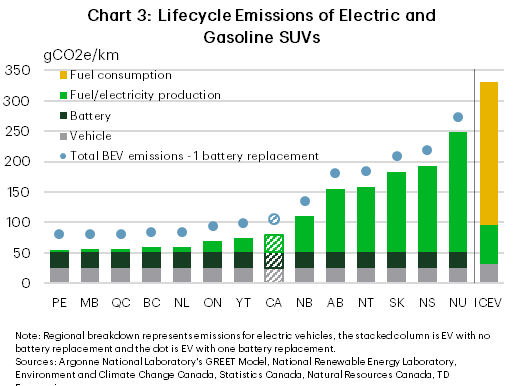

The emissions advantage of using a full electric vehicle over a gasoline vehicle varies across regions, depending on the carbon intensity of the electricity grid. In the case of SUVs, BEV lifecycle emissions are, on average, 76% lower at the national level compared to gasoline SUVs.

The regional savings range from 25% in Nunavut (which relies on petroleum for power) to 78-83% in regions that generate most of their electricity with hydroelectric facilities (such as Quebec, Manitoba, British Columbia, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Yukon). Ontario also sees savings around 80%, where nuclear, hydro, and renewables account for almost 90% of domestic electricity generation.

Even in provinces with more emission-intensive grids such as Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut, BEVs remain beneficial in reducing transportation emissions, because they require, on average, less energy to operate than gasoline vehicles.

Chart 3 shows average lifecycle emissions of gasoline versus battery electric SUVs in different parts of Canada.

A significant factor affecting EV lifecycle emissions is battery degradation. With approximately 85% of BEVs registered in Canada since 2011 (as of Q3 2024) sold in the last five years, the long-term lifespan of lithium-ion batteries is unclear. Nevertheless, even with the inclusion of battery replacement, it only slightly reduces emissions savings. For SUVs, the national emissions savings decrease to 68%, with the range for the provinces and territories declining to 17% to 75%.

PHEVs

Chart 4 shows average lifecycle emissions of gasoline versus plug-in hybrid electric SUVs in different parts of Canada.

Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) have lower average emissions compared to ICEVs, but their environmental benefits are less than those of BEVs. The degree to which PHEVs utilize electric mode driving versus gasoline-mode driving is important for emissions savings.

According to a BloombergNEF study, private PHEVs are driven in electric mode 26-54% of the time, while company cars are driven in electric mode 11-24% of the time.

For privately-owned SUVs, for example, using electric mode 54% of the time reduces lifecycle emissions by 11-53% depending on the part of the country and the grid’s carbon intensity, with electric mode driving yielding average emissions savings of 12-33%.

Affordability and Policy

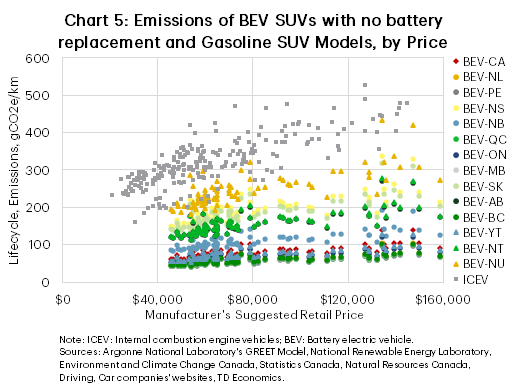

Chart 5 is a scatter plot showing lifecycle emissions of individual gasoline and battery electric SUV models against the manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP).

The average emissions estimates by vehicle class mask some variations between different vehicle models and price points. Across price ranges where there is some overlap between EVs and gasoline vehicles, most BEV models have lower lifecycle emissions than comparable gasoline models—except for a few models that are found in jurisdictions with high-emitting electricity grids.

However, there is a lack of BEV models across the model range used in the analysis. Because the lack of models makes it hard to switch to electric vehicles for the consumers who can’t afford the more costly models, this shortage affects a group of consumers in the same way. This problem is likely to be exacerbated by the recent end of the federal zero-emission vehicles rebate program. Thus there is indication for the need to widen and expand rebate programs to lower-income buyers.

Conclusion

BEVs offer significant emissions advantages compared to ICEVs and can play an important role in decarbonizing transportation. Full electric vehicles generally have lower lifecycle emissions, including in provinces and territories that have high-emitting electricity generation. Because of this potential to generate additional emissions savings, the variance in lifecycle emissions, caused by distinct differences in the regional electricity supply mix, highlights the need for the decarbonization of the electricity sector.

Although PHEVs can also be helpful for lessening emissions, the total savings are less compared to BEVs. In addition, PHEVs are most beneficial when a larger share of driving is done in electric mode—where electric mode is used infrequently, the benefits decrease. Finally, it is essential to have more affordable electric models available in the market to compete with gasoline vehicles and expand access to consumers purchasing vehicles in the lower price ranges. This means there are also needs for expanding rebate programs to help improve the affordability of lower-priced gasoline vehicles as well.