The Electric Avenue: China’s EV Invasion

If you’re planning to buy an electric car soon, you might be tempted by a less familiar brand from China, rather than the established names like Ford or Volkswagen. The Hedgehog E400, Zotye i-across, or Ora Funky Cat might seem appealing.

Chinese electric cars are arriving, and they’re coming in strong. Brands like Zeekr, SAIC, Geely, Great Wall, Fengon, and Foton have been present in China for years, and they’re poised to become commonplace on roads worldwide.

It’s not the first time competition has come from East Asia. Back in the 1960s, when cars had British names, imports from Japan started appearing with unfamiliar names. First came Daihatsu, then Datsun, Mazda, Honda, and the Toyota, which sounded the strangest of all.

In 1969, my father, always a fan of gadgets and bargains, swapped his Vauxhall Victor for a Toyota Crown Estate, loaded with features we’d never seen. Central locking! Electric windows! The friendly mechanic at the dealership in London tried to dissuade him.

“They’re just poor copies of British cars, made of cheaper materials. The clue is in the name – TOY-ota.”

However, it turned out to be a great car: reliable and fast. It was such a rare sight that it drew crowds wherever we went.

Chinese electric cars, packed with technology and looking good, are set to outsell Western brands on price – some may cost under £10,000. BYD, the top-selling Chinese EV brand, has already surpassed Tesla. BYD double-deckers are already in London, even if they’re built in Falkirk.

Beyond the Budget: Security Concerns

But, there’s a significant question about electric cars from China: are they Trojan horses filled with electronics to spy on aspects of life in the West?

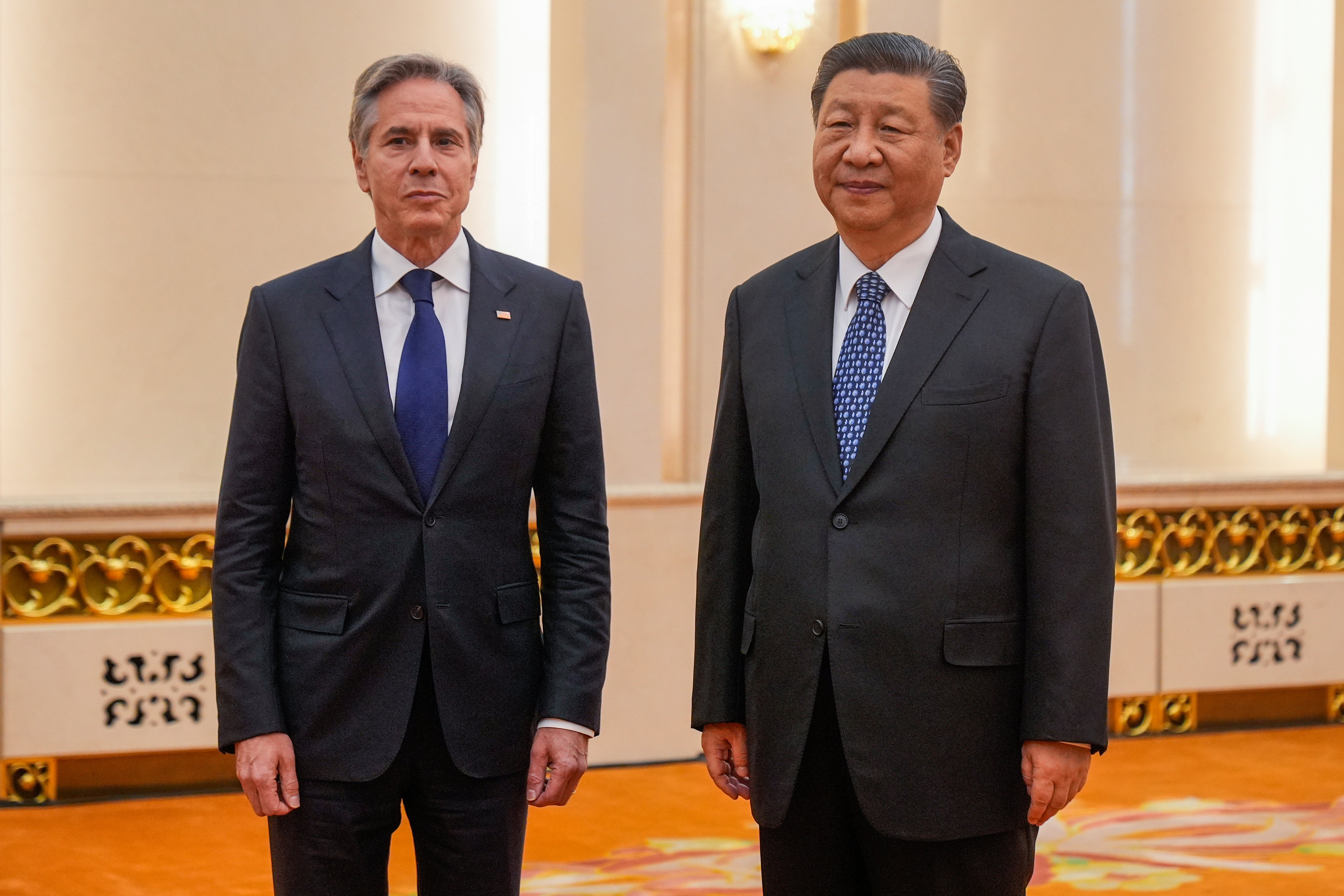

Former US President Biden singled out Chinese cars and trucks as a national security risk last year. His Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, discussed China allegedly dumping cheap EVs in the West with the Chinese government last week.

The concern centers on the fact that EVs are always connected to the internet, functioning like data-collecting mobile phones. A Hong Kong-born reader of a New York Times article expressed security concerns.

“Don’t any of you remember why we banned Chinese-designed Huawei and ZTE telecommunications equipment from becoming part of our phone and network infrastructure?

Now imagine thousands of internet-connected Chinese programmed computers in control of your Chinese-made cars roaming the country spying, spreading computer viruses, sending your travel history, maybe even everything you say, Alexa-style, to China.”

This reader concluded: “I know that introducing Chinese programmed cars alone won’t overthrow US democracy, but why deliver one more weapon into the hands of a known hostile power?”

The possibility of your new, affordable Hedgehog being a risk is unnerving. However, having worked with Chinese firms, I question if this is a real threat or a moral panic, used by the White House to signal its concern for American carmakers and their workers?

It’s plausible that the Communist Party desires internet-connected cars to be hackable. But my experience suggests that many Chinese people and businesses view the Party as a nuisance.

For many in China, making money, being with family, getting an education, and having fun come before seeking global domination. So, while it might be necessary to convince officials that a BYD model can be brought to a halt, the detailed programming may not be done with much care.

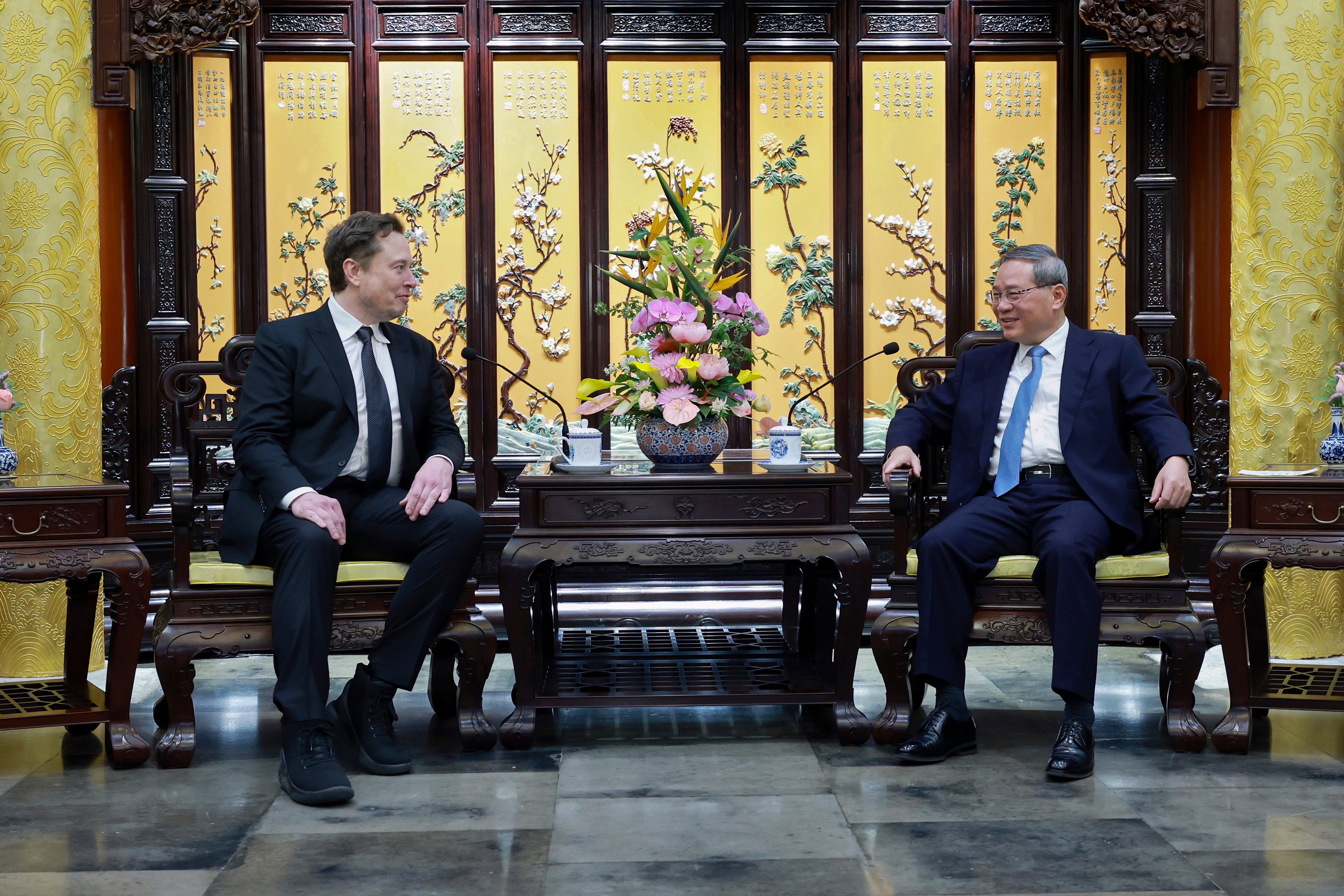

That’s not to suggest that Chinese entrepreneurs, whether state-owned or private, aren’t enthusiastic about electric cars. They have viewed our backwardness in sustainable transport as pathetic for two decades.

A sign of China’s focus on clean transport is displayed on a giant screen at BYD’s headquarters, asking “Where is Noah’s ark that saved mankind?” Electric cars are also more exciting career options. BYD stands for “Build Your Dreams”, their company mission.

Would a real China expert agree that those designing and making EVs and programming their technology to spy on the West see it as a tiresome duty?

I consulted Dr. Ilaria Mazzocco, Senior Fellow in Chinese Business and Economics at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC.

“I went to the Shanghai Electric Vehicle Public Data Collecting, Monitoring, and Research Center a few years ago,” said Dr. Mazzocco. They showed me a screen with trackers on every EV registered in Shanghai and knew their exact locations.

“They were using this data to figure out how people were charging cars and how to be more efficient. But, yes, you could imagine how that data could be used for very different reasons.”

“It’s clear that BYD has a world domination strategy. It’s probably coming from the BYD headquarters. It certainly seems to be aligned with what Beijing would like as well. However, the sort of regulation in China that expands the power of the Party is not helpful to tech companies trying to become multinationals and convince the rest of the world that they’re just profit-driven normal companies. So in terms of the back-door capabilities, and how enthusiastic Chinese companies might be about it, my suspicion is that they would probably not be super enthusiastic, because it might cost them a lot of market share if it came out. But the real question is, would they do it? And I think the answer, we all know, is probably yes.”