The Steel Revolution: How New Materials are Reshaping Cars

Every bit of weight saved in a car helps, whether it’s lowering fuel consumption in gas-powered vehicles or extending the range of electric vehicles.

Like many breakthroughs, creating high-quality steel may have been a mix of skill and accidental discovery. Centuries ago, firing iron with charcoal in a special clay container produced wootz steel. Today, automakers are using advanced methods to modify steel for safety and efficiency, reducing the environmental impact.

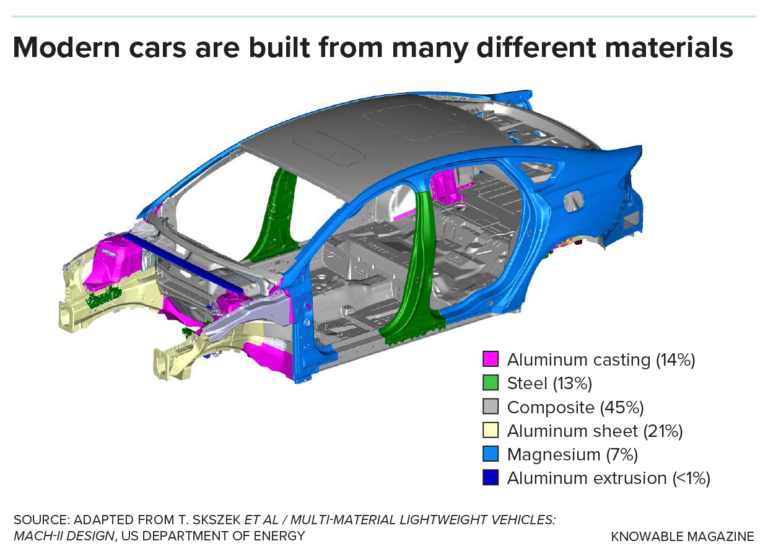

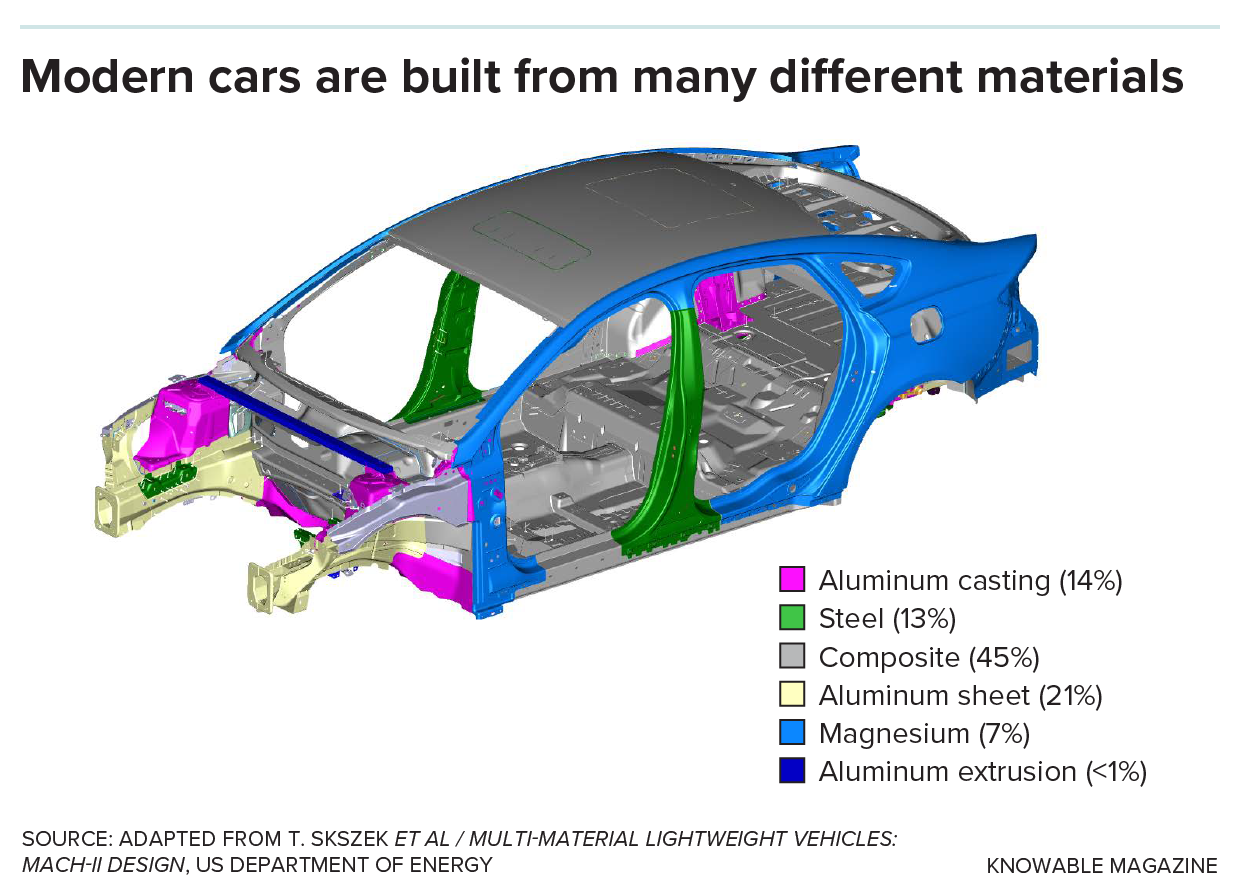

“It’s a revolution,” says Alan Taub, a University of Michigan engineering professor. New steels, combined with lightweight polymers and carbon fiber, are helping to reduce vehicle weight.

These new materials can trim hundreds of pounds off a vehicle, saving roughly $3 in fuel costs for every pound shed over its lifespan. Electric vehicles benefit from these new materials, as the technology itself adds weight. Lightweighting helps boost the range of EVs— a 10 percent weight reduction can provide roughly a 14 percent increase in range.

The Evolution of Auto Steel

In the 1960s, the safety cage around passengers was made of what automakers called soft steel, which was heavy. The oil embargoes of the 1970s sped up the need for change, spurring the need for steel that was both stronger and lighter.

Over the past 60 years, steelmakers have developed various types of steel to match every need. Advanced steels are now used for the chassis, corrosion-resistant steels for side panels, and highly stretchable metals in bumpers to absorb impact without crumpling.

Steel’s Secrets

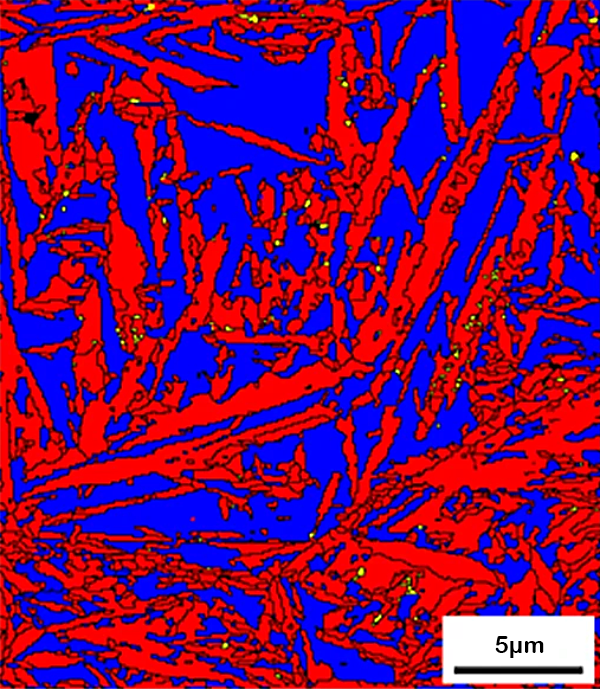

Most steel is more than 98 percent iron. It’s the other couple of percent—sometimes only hundredths of a single percent, in the case of metals added to confer desired properties—that make the difference. The heating, cooling, and processing methods also change a metal’s structure to yield different properties. “It’s all about playing tricks with the steel,” says John Speer, director of the Advanced Steel Processing and Products Research Center at the Colorado School of Mines.

At the atomic level, there are four main phases of auto steel, including the hardest, most brittle martensite, and the more ductile austenite. Automakers adjust heating and cooling temperatures to get the properties they need.

Advancements in High-Strength Steel

Researchers and steelmakers have developed three generations of advanced high-strength steel. The third generation uses heating and cooling to produce steels that are stronger and more formable than older versions, while also being cheaper than earlier iterations.

Cooling time is critical. Rapid cooling, known as quenching, freezes and stabilizes the metal’s structure. An important type of modern auto steel is made by superheating the metal with boron and manganese to a temperature above 850 degrees Celsius, then rapidly cooling it.

Beyond Steel: The Role of Alloys and Composites

Various alloys can further modify the metal’s properties. Henry Ford was using steel and vanadium alloys over a century ago. Modern examples use lighter metals, such as the Ford Motor Company’s aluminum-intensive F-150 truck, introduced in 2015.

A process that works with new materials is tube hydroforming. This process uses high-pressure injection of water into a tube, expanding it into the shape of a die. This allows for parts to be made without welding two halves together, saving time and money.

The Future of Automotive Materials

More recent developments include alloys that use titanium and niobium. Computer simulations are also helping to speed up the development of new materials.

Institutes dedicated to research are working on finding better replacements, such as climate friendly alternatives for conventional plastics. Plastics are ideal for automakers, because they have a high strength-to-weight ratio.

Research is underway to create stronger, lighter, and more environmentally friendly plastics. At the same time, new carbon fiber products are enabling even load-bearing structural underbody parts. Clearly there is work to be done, but the future looks bright.